Deep circulation flows

Storyboard

There are several points where flows from the ocean surface to greater depths occur, inducing deep circulation. This circulation is subject to the Coriolis force, resulting in deviations and some flows towards the surface (upwelling) that are associated with surface currents.

The classic model for these currents is that of Stommel and Arons, which, although simple, explains the different depth flows observed.

[1] Ocean Circulation Theory, Joseph Pedlosky, Springer 1998 (7.3 Stommel-Arons Theory: Abyssal Flow on the Sphere)

ID:(1623, 0)

Deep circulation flows

Storyboard

There are several points where flows from the ocean surface to greater depths occur, inducing deep circulation. This circulation is subject to the Coriolis force, resulting in deviations and some flows towards the surface (upwelling) that are associated with surface currents. The classic model for these currents is that of Stommel and Arons, which, although simple, explains the different depth flows observed. [1] Ocean Circulation Theory, Joseph Pedlosky, Springer 1998 (7.3 Stommel-Arons Theory: Abyssal Flow on the Sphere)

Variables

Calculations

Calculations

Equations

As the coriolis acceleration in x direction ($a_{c,x}$) is composed of the angular velocity of the planet ($\omega$), the latitude ($\varphi$), the speed y of the object ($v_y$), and the speed z of the object ($v_z$):

and the definition of the coriolis factor ($f$) is:

in addition to the constraint of movement on the surface where:

$v_z = 0$

this leads to the coriolis acceleration in x direction ($a_{c,x}$) being:

Since the coriolis acceleration in y direction ($a_{c,y}$) is composed of the angular velocity of the planet ($\omega$), the speed x of the object ($v_x$), and the latitude ($\varphi$):

and the definition of the coriolis factor ($f$) is:

in addition to the constraint of movement on the surface where:

$v_z = 0$

this leads to the coriolis acceleration in y direction ($a_{c,y}$) being:

If we introduce typical timescales for each dimension, we can estimate the Coriolis accelerations as velocities divided by their typical timescales, that is:

$v_i =a_i \Delta t_i$

with

Thus, we have:

$v_z=\beta R v_x\Delta t_z$

On the other hand, with the equation for the

$v_x=\displaystyle\frac{v_y}{f\Delta t_y}$

By replacing

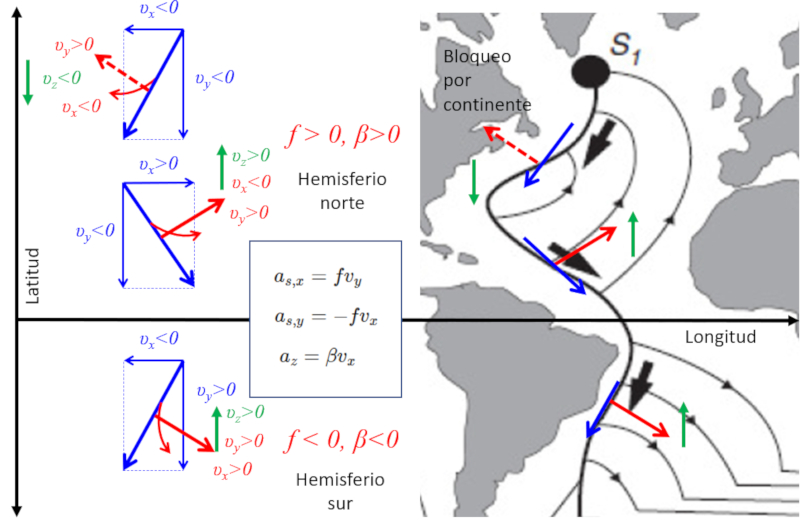

When there is movement in the x-direction (east-west), it results in the coriolis acceleration in z direction ($a_{c,z}$) with the speed x of the object ($v_x$), the angular velocity of the planet ($\omega$), and the latitude ($\varphi$):

This is complemented by the coriolis acceleration on the surface, in the x direction ($a_{c,x}$) (east-west), with the coriolis factor ($f$) and the speed y of the object ($v_y$):

and the coriolis acceleration on the surface, in the y direction ($a_{c,y}$) (north-south) with the coriolis factor ($f$) and the speed x of the object ($v_x$), which is:

Where the coriolis factor ($f$) is defined as:

Therefore, we can introduce the coriolis Beta Factor ($\beta$), defined as:

With this, we obtain:

In analogy to the coriolis factor ($f$) defined with the latitude ($\varphi$) and the angular velocity of the planet ($\omega$) as:

the factor varies in the arc $R\theta$, with the planet radio ($R$) and the latitude ($\varphi$) as the latitude, according to:

$\displaystyle\frac{\partial f}{\partial (R\varphi) }=\displaystyle\frac{ 2\omega\cos\varphi }{R}$

thus the coriolis Beta Factor ($\beta$) can be defined as:

Examples

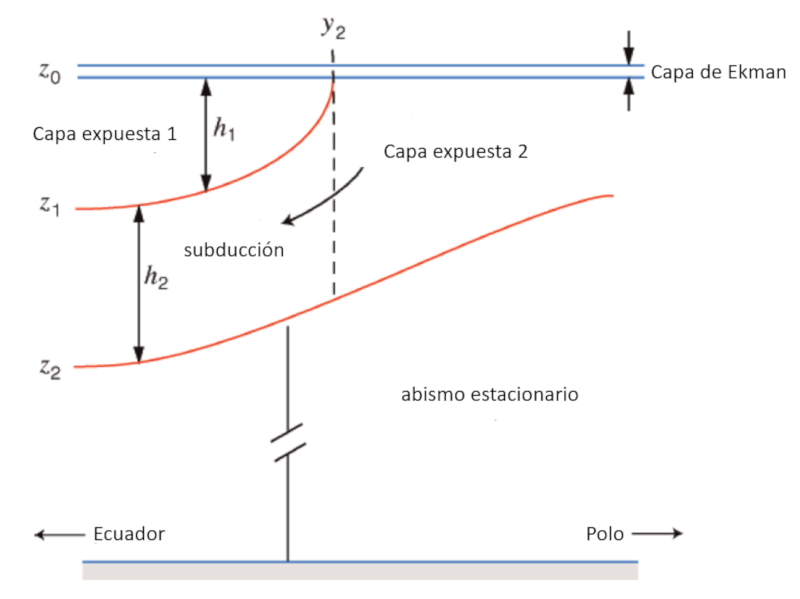

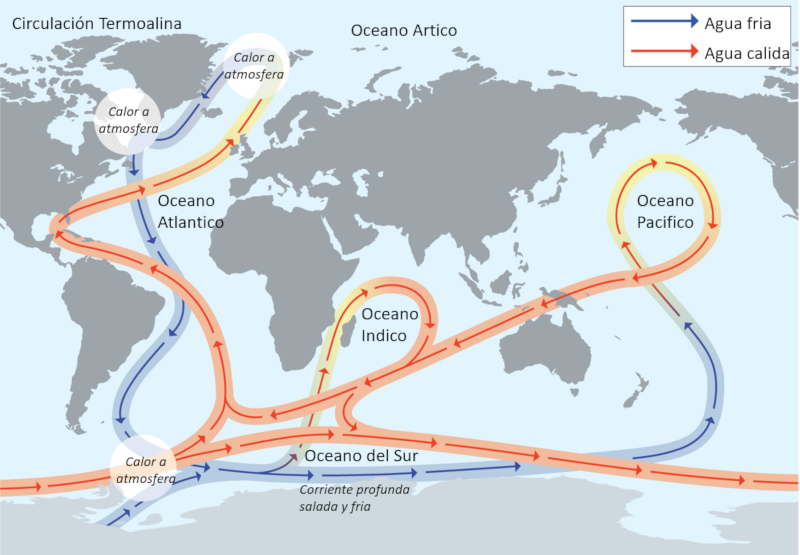

The deeper circulation is known as thermohaline circulation (THC) because its movement is associated with variations in temperature (thermo) and salinity (haline). To understand how this occurs, we must first describe the structure of the system.

In a simplified form, the ocean can be modeled as a three-layer system:

- An upper layer where water movement is generated by wind-driven currents.

- An intermediate layer where movement is driven by density differences in the ocean, originating from variations in temperature and salinity (thermohaline).

- A deep layer that can be assumed to be at rest.

The increase in density towards the poles, where the water is colder, causes the water to literally sink, creating subduction beneath the surface layer. The following diagram summarizes the described process:

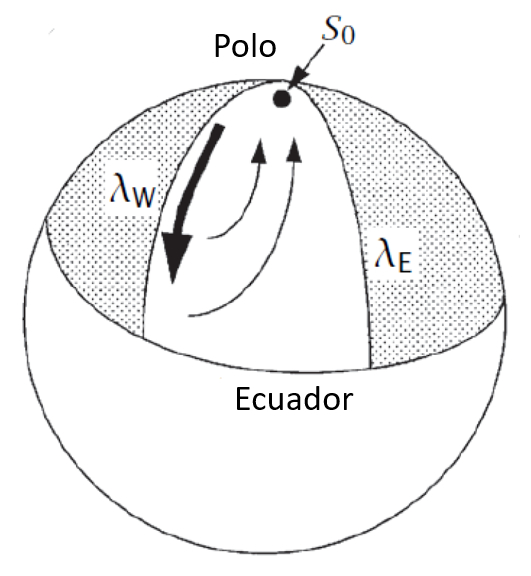

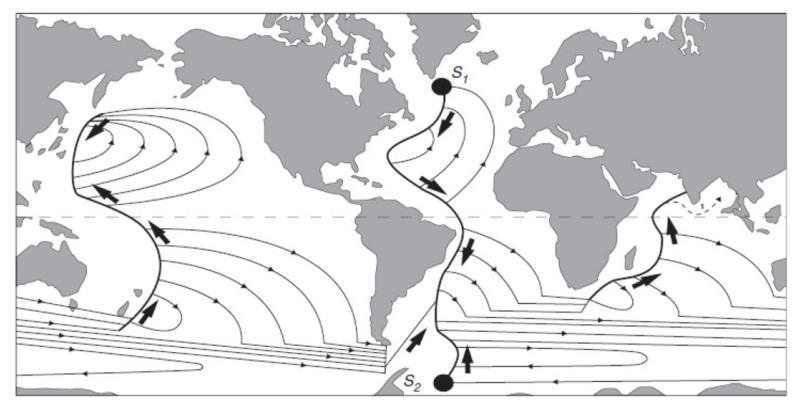

If we observe the globe, the thermohaline circulation is generated near one of the poles (north or south) through water that, due to higher salinity and lower temperature, begins to sink. Its flow is directed towards the equator, creating an upwelling where water partially rises and flows towards the pole to replenish the descending water.

[1] Stommel, H., & Arons, A. B. (1960). On the abyssal circulation of the world oceanI. Stationary planetary flow patterns on a sphere. Deep Sea Research (1953), 6(2), 140-154.

[2] Stommel, H., & Arons, A. B. (1960). On the abyssal circulation of the world oceanII. An idealized model of the circulation pattern and amplitude in oceanic basins. Deep Sea Research (1953), 6(3), 217-233.

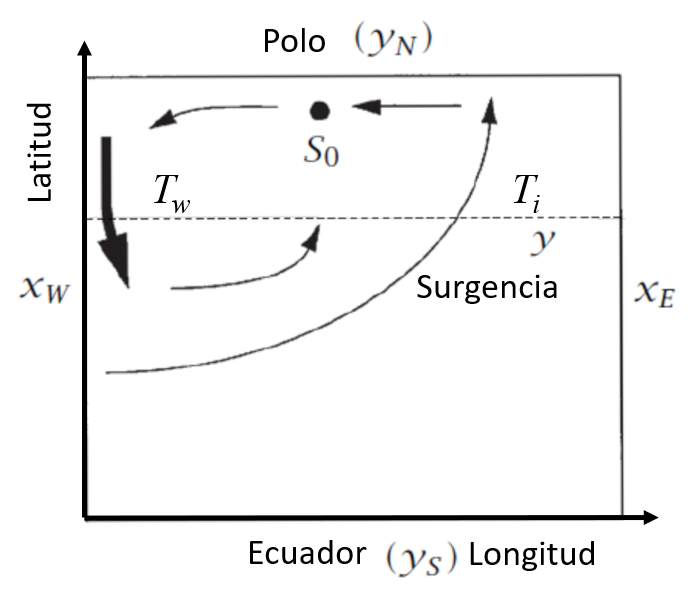

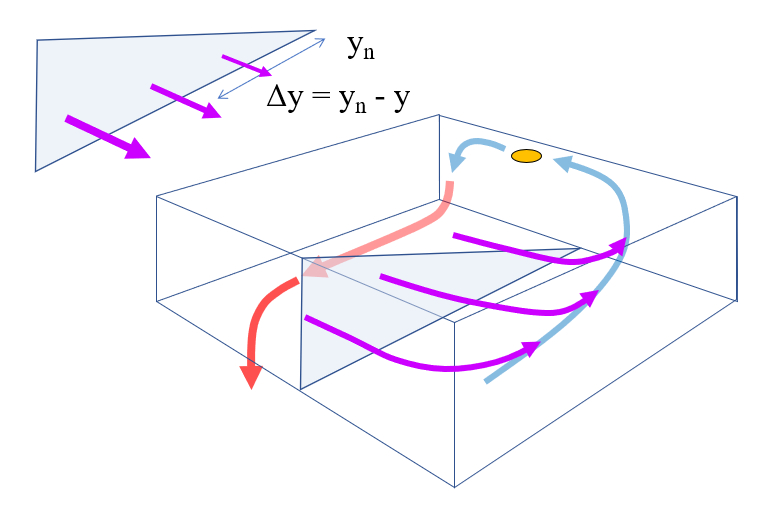

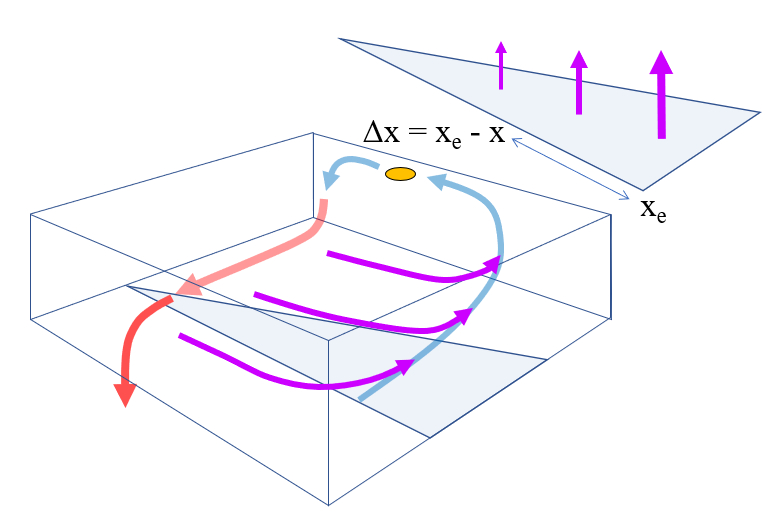

The Stommel and Arons model [1], [2] considers the ocean as a two-dimensional box with coordinates on the x and y axes. Specifically:

- Coordinates on the x-axis: $x_w$ (west) and $x_e$ (east).

- Coordinates on the y-axis: $y_s$ (south) and $y_n$ (north).

These coordinates are represented in the following graph:

[1] Stommel, H., & Arons, A. B. (1960). On the abyssal circulation of the world oceanI. Stationary planetary flow patterns on a sphere. Deep Sea Research (1953), 6(2), 140-154.

[2] Stommel, H., & Arons, A. B. (1960). On the abyssal circulation of the world oceanII. An idealized model of the circulation pattern and amplitude in oceanic basins. Deep Sea Research (1953), 6(3), 217-233.

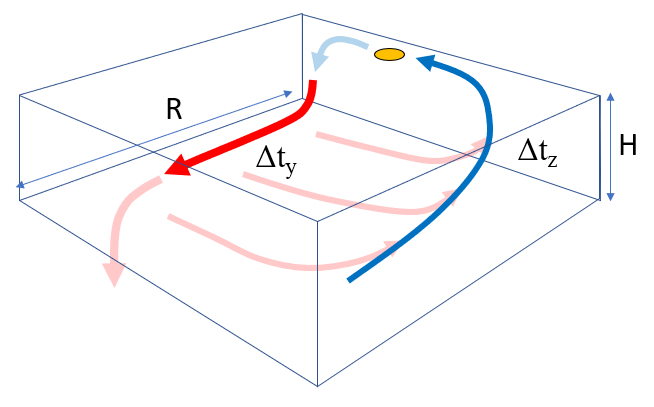

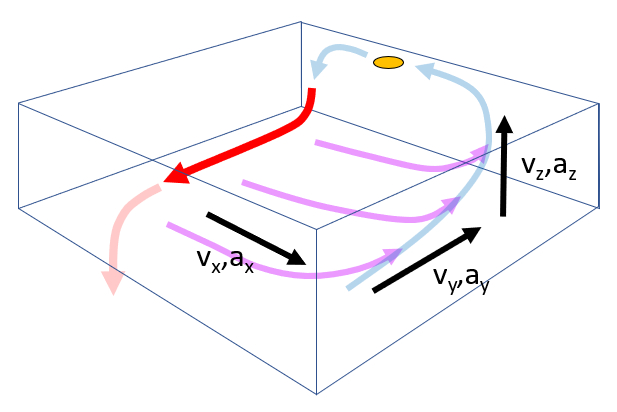

Each stage is associated with a characteristic time:

- Travel time with the main flow $\Delta t_y$

- Deflection time with the loss flow $\Delta t_x$

- Upwelling time $\Delta t_z$

Each characteristic time is associated with velocities and accelerations along the traveled path:

- With the main flow $v_y, a_y$.

- With the loss flow $v_x, a_x$.

- With the upwelling $v_z, a_z$.

Generally, the initial velocity (

The loss flow is not uniform and is distributed along the latitude, so it is modeled based on its distance from the northernmost position. Thus, it is zero at northern latitudes and maximum at the southern edge of the rectangle where the circulation is modeled:

Since the loss flow is not uniform, neither is the upwelling. Within the same model, it is assumed that the upwelling is maximum at the eastern edge of the rectangle where the circulation is modeled. Similar to the loss, a linear relationship is assumed:

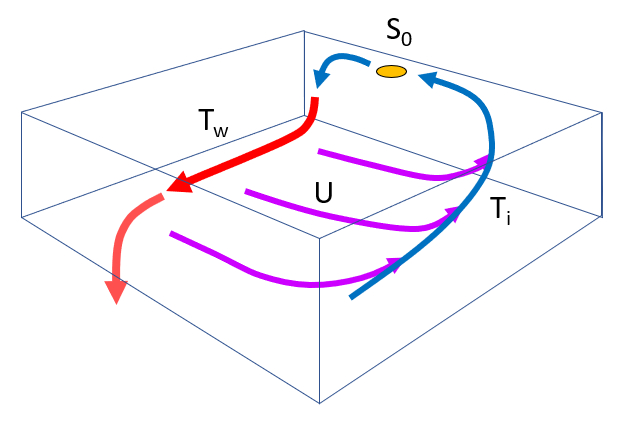

There are four flows to consider in modeling deep flow:

The main flow $F_w$, which moves along the seafloor.

The loss flow $F_i$, which is the fraction deviated due to the Coriolis force.

The upwelling flow $U_x$, which corresponds to the fraction of loss flow reaching the surface.

The sinking flow $S_0, originating from surface currents, including losses that sink again.

The so-called Coriolis force plays an essential role in the dynamics of water in the poles, influencing how water masses descend due to variations in temperature and salinity.

When analyzing the Atlantic Ocean, one can observe a movement of water from the pole towards the equator, which deflects towards the west. This phenomenon is caused by the lag relative to the planet\'s rotation, as it transitions from a zone of slower speed along the latitude to one of higher speed. This behavior can be modeled using the Coriolis equation for the x-direction, given by

In this equation, the Coriolis factor

The geographical contour of the continent allows for movement in the x-direction (longitude), resulting in an acceleration in the y-direction (latitude), which can be calculated using

This calculation reveals that near the equator, displacements occur that take water away from the main current, moving it northward. If we examine the acceleration in the z-direction (depth) and take into account that

At the end, Stommel and Arons [1], [2] solve the model, indicating the main deep flows that exist throughout the globe:

[1] Stommel, H., & Arons, A. B. (1960). On the abyssal circulation of the world oceanI. Stationary planetary flow patterns on a sphere. Deep Sea Research (1953), 6(2), 140-154.

[2] Stommel, H., & Arons, A. B. (1960). On the abyssal circulation of the world oceanII. An idealized model of the circulation pattern and amplitude in oceanic basins. Deep Sea Research (1953), 6(3), 217-233.

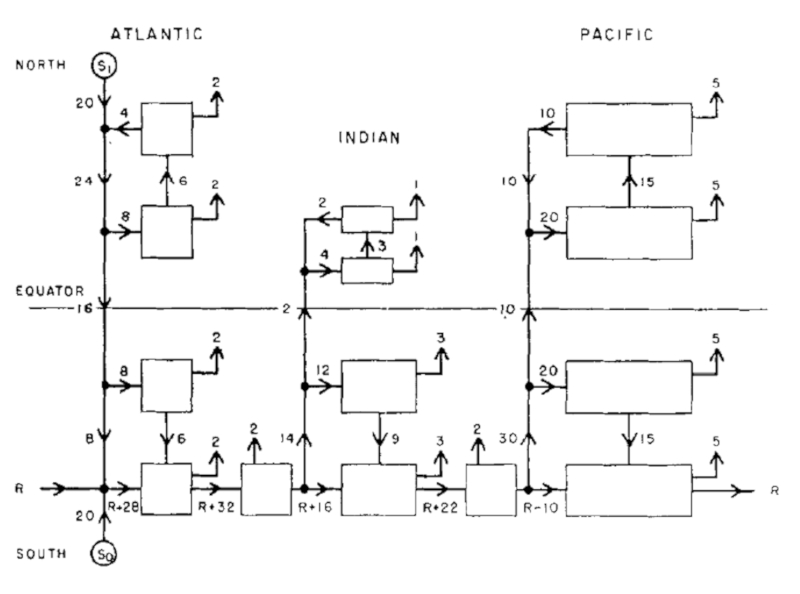

When Stommel and Arons [1], [2] developed their first model of thermohaline circulation, they subdivided the different oceans into zones with defined upwelling (upward arrows) and two sources, one in the Arctic and the other in Antarctica:

[1] Stommel, H., & Arons, A. B. (1960). On the abyssal circulation of the world oceanI. Stationary planetary flow patterns on a sphere. Deep Sea Research (1953), 6(2), 140-154.

[2] Stommel, H., & Arons, A. B. (1960). On the abyssal circulation of the world oceanII. An idealized model of the circulation pattern and amplitude in oceanic basins. Deep Sea Research (1953), 6(3), 217-233.

Measurements have shown that the thermohaline circulation is an integrated system that spans the entire globe. It has at least two points that can be considered as sources, and its path extends across all the oceans.

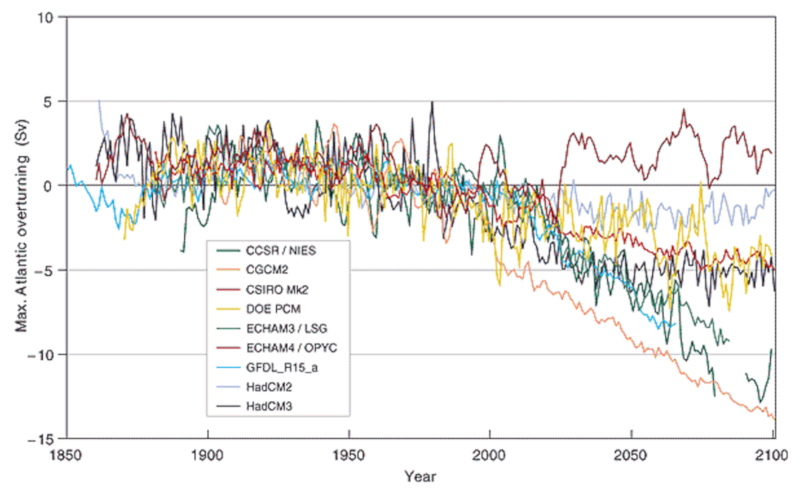

Through multiple simulations, the effects of polar ice melting on the suppression of sinking and its impact on deep circulation are studied. There are indications that circulation has started to decline; however, the collapse of deep circulation does not necessarily imply the same will happen to surface circulation, which is driven by winds. What could happen is a shift in the surface circulation, resulting in a reduction of the Gulf Stream's contribution of warm waters to northern Europe.

The diagram below shows variations in flow in units of Sv (Sverdrup), which is equivalent to $10^6,m^3/s$:

Assuming a sinking rate of approximately 20 Sv, it is concluded that in some simulations, deep circulation comes to a halt. These variations are associated with different future scenarios of human activity and considerations for aspects with less certainty about their occurrence. More detailed information can be found in the reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

When modeling the North Atlantic as a box with a coordinate system close to the equator and in the Caribbean region, the width of the box is calculated by subtracting the west position from the east position:

To model the North Atlantic as a box with a coordinate system close to the equator and in the Caribbean region, the height of the box is determined by subtracting the southern position from the northern position:

In analogy to the Coriolis factor, we can study how the factor varies along the arc, leading us to obtain the coriolis Beta Factor ($\beta$) given by the latitude ($\varphi$), the planet radio ($R$), and the angular velocity of the planet ($\omega$) by:

Based on the relationship between the Coriolis acceleration and the velocities in each axis, we can estimate the acceleration of upwelling that will occur in the circulation. Using the parameterization that depends on the sector size and latitude of the location, we obtain the coriolis acceleration in z direction ($a_{c,z}$) as a function of the coriolis Beta Factor ($\beta$), the planet radio ($R$), and the parallel speed ($v_x$):

As the coriolis acceleration in x direction ($a_{c,x}$) can be rewritten with the coriolis factor ($f$) and under the condition that there is no vertical movement:

$v_z = 0$

Therefore, it follows that the coriolis acceleration on the surface, in the x direction ($a_{c,x}$) is:

Since the coriolis acceleration in x direction ($a_{c,x}$) can be rewritten with the coriolis factor ($f$) under the condition that there is no vertical movement:

$v_z = 0$

Then, it follows that the coriolis acceleration on the surface, in the y direction ($a_{c,y}$) is:

Movement along a latitude, due to Earths rotation, generates a Coriolis acceleration the coriolis acceleration on the surface, in the y direction ($a_{c,y}$), which in the characteristic time interval movement in $y$ ($\Delta t_y$) results in the speed in meridian ($v_y$) according to:

The upwelling velocity the upwelling speed ($v_z$) is determined by the coriolis acceleration in z direction ($a_{c,z}$) as a function of the characteristic time interval movement in $z$ ($\Delta t_z$):

To simplify the equations, we work with ERROR:8600.1, which is a constant for the physical location, as it includes the angular velocity of the planet ($\omega$) for the Earth and the latitude ($\varphi$) for the location:

In the southern hemisphere, the latitude is negative, and with it, 8600, explaining why systems rotate in the opposite direction to the northern hemisphere.

The circulation of the flow causes the parallel speed ($v_x$) to tend to have a magnitude similar to the speed in meridian ($v_y$) in a negative gyre:

The continuity of flow allows us to determine how velocities are related in each phase. In this way, we can estimate the upwelling speed ($v_z$) based on the coriolis Beta Factor ($\beta$), the coriolis factor ($f$), the characteristic time interval movement in $y$ ($\Delta t_y$), the characteristic time interval movement in $z$ ($\Delta t_z$), the planet radio ($R$), and the speed in meridian ($v_y$):

As the upwelling velocity is determined by

and the relationship between the times must comply with

the velocity at the bottom is given by

The upwelling depends on the velocity towards the surface and the position within the box. Since it is greater towards the equator and relatively uniform across the width, it is modeled to vary only with the distance to the northern edge of the box:

$y_n - y$

Therefore, with

The upwelling velocity is determined using the value

The flow inside the box can be modeled using the equation

.

Specifically, it is observed that the upwelling velocity is higher towards the western edge, which can be represented with

The presence of the factor 2 in the model accounts for taking an average considering the existing gradient.

The time in the

The conservation of flow implies that the flow moving along the east coast of America, denoted as $T_w$, and the upwelling components, represented by $U_x$, are initially generated by the sinking volume, indicated as $S_0$, in addition to those coming from circulation through upwelling. Therefore, we can express it as follows:

In this case, there are two types of flows: surface flow and flow towards or from the depth. By conservation, we can assume that the total flow flowing towards the depths at point S_0 should correspond to the total flow generated by the upwelling. The latter occurs over the entire surface and with vertical velocity, so:

If the velocity is multiplied by

with the height

$T_i \sim v_y H \Delta x$

So, with

Unter Ber cksichtigung der Bilanzgleichung mit

und dem Beitrag der Quelle mit

sowie dem Hintergrundfluss mit

und der Auftriebsstr mung mit

nehmen wir an, dass die Zone den quator erreicht (

Since the Coriolis factor is given by

it can be related to the beta factor based on its variation around a position. This is because, in the Taylor expansion, we obtain:

$f \sim f_0 + \frac{df}{dy}y$

where the derivative is:

$\frac{df}{dy} = 2\omega\cos\theta = \beta$

Thus, with

With

can be rewritten as

using

ID:(1623, 0)