Entropy

Storyboard

Entropy is the portion of energy in a system that cannot be used to perform work. From a microscopic perspective, it is related to the number of possible configurations that the system can assume. A greater number of these configurations is associated with an increase in the disorder of the system and a decrease in the probability that it will return to a previous state, thereby reducing the possibility of the system's reversibility.

ID:(1471, 0)

Mechanisms

Definition

Physical entropy is a fundamental concept in thermodynamics and statistical mechanics that represents the degree of disorder or randomness in a system. It measures the number of specific ways a thermodynamic system can be arranged, reflecting the amount of uncertainty or the number of possible microstates corresponding to a given macrostate. Entropy quantifies disorder, with higher entropy indicating greater disorder. According to the second law of thermodynamics, the entropy of an isolated system never decreases, meaning natural processes tend to move toward a state of maximum entropy or disorder. Entropy also measures the irreversibility of processes, where spontaneous processes increase the entropy of the universe. It is a key factor in determining the efficiency of heat engines and refrigerators, understanding the behavior of biological systems, and studying the evolution of the universe. In essence, entropy is a measure of the unpredictability and energy dispersion in a system, providing insight into the natural tendency towards disorder and the limitations of energy conversion.

ID:(15246, 0)

Types of variables

Image

If we consider the equation of the differential inexact labour ($\delta W$) with the mechanical force ($F$) and the distance traveled ($dx$):

| $ \Delta W = F \Delta s $ |

in its form of the pressure ($p$) and the volume ($V$):

| $ \delta W = p dV $ |

Work plays the role of a potential, while the pressure ($p$) acts as a 'generalized force,' and the volume ($V$) serves as the path, a kind of 'independent variable.' If we organize these concepts into a matrix for the parameters we have discussed so far, we get:

| Thermodynamic Potential | Generalized Force | Independent Variable |

| Extensive | Intensive | Extensive |

| $\delta W$ | $p$ | $dV$ |

| $\delta Q$ | $T$ | $?$ |

In this context, we see that for the line the variation of heat ($\delta Q$), we have the variable the absolute temperature ($T$), but we lack an extensive independent variable. We will call this entropy and denote it with the letter $S$.

ID:(11183, 0)

Intensive and extensive variables

Note

There are variables that are associated with quantities, while others are associated with properties.

• The first ones are called extensive variables, as they can be extended or increased in proportion to the amount of substance present. Examples of extensive variables include volume, mass, electric charge, heat, and so on.

• On the other hand, the second ones are called intensive variables, which represent properties that do not depend on the quantity of substance present. These properties remain unchanged regardless of the amount of substance. Examples of intensive variables include density, pressure, temperature, and so on.

ID:(11182, 0)

Entropy and Phase Change

Quote

If the entropy is estimated as a function of temperature, the following observations can be made:

• In each phase (solid, liquid, gas), entropy tends to slightly increase with temperature.

• During phase transitions, there is a significant jump in entropy.

This can be represented as:

In this way, entropy can be understood as an average measure of the degrees of freedom that a system possesses. In each phase, entropy gradually increases as a few additional degrees of freedom are \\"released\\". However, during phase transitions, the increase in entropy is dramatic. In a solid, multiple bonds restrict the movement of atoms, resulting in limited degrees of freedom. In a liquid, many bonds are broken, creating new freedoms that allow for relative movement, leading to numerous new degrees of freedom. Finally, in the transition to the gas phase, all bonds are lost, and each particle has its three degrees of freedom. As the temperature increases further, particles can rotate and oscillate, introducing new degrees of freedom and additional increases in entropy.

ID:(11187, 0)

Entropy and Irreversibility

Exercise

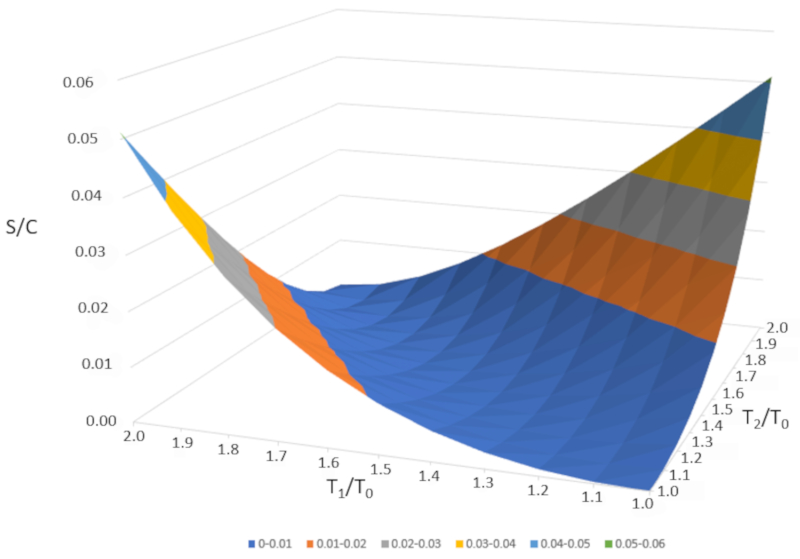

If we consider two identical systems, one with a temperature $T_1$ and the other with a temperature $T_2$, their entropies can be calculated using the equation involving the entropy ($S$), the absolute temperature ($T$), the caloric Capacity ($C$), the base entropy ($S_0$), and the base temperature ($T_0$):

| $ S = S_0 + C \log\left(\displaystyle\frac{ T }{ T_0 }\right)$ |

Therefore, the entropies will be:

$S_1 = S_0 + C\log\left(\displaystyle\frac{T_1}{T_0}\right)$

and

$S_2 = S_0 + C\log\left(\displaystyle\frac{T_2}{T_0}\right)$

If both systems are mixed, their temperature will be the average temperature:

$T_m=\displaystyle\frac{1}{2}(T_1+T_2)$

Therefore, the entropy of the new system will be:

$S_{1+2}=2S_0+2C\log\left(\displaystyle\frac{T_m}{T_0}\right)=2S_0+2C\log\left(\displaystyle\frac{T_1+T_2}{2T_0}\right)$

The entropy of the new system is greater than the sum of the individual entropies:

$\Delta S=2C\log\left(\displaystyle\frac{T_1+T_2}{2T_0}\right)-C\log\left(\displaystyle\frac{T_1}{T_0}\right)-C\log\left(\displaystyle\frac{T_2}{T_0}\right)$

If we graph $\Delta S/C$ as a function of $T_1/T_0$ and $T_2/T_0," we obtain the following figure:

$\Delta S/C$ is nearly zero if the temperatures are very similar ($T_1\sim T_2$). However, if the temperatures are different, entropy will always increase. If we study this in other systems, we will observe that whenever an irreversible change occurs, entropy increases. Mixing is irreversible, meaning the system will not return to its initial state without external intervention. In other words, the system will not spontaneously separate into two subsystems with completely different temperatures.

ID:(11186, 0)

Entropy

Storyboard

Physical entropy is a fundamental concept in thermodynamics and statistical mechanics that represents the degree of disorder or randomness in a system. It measures the number of specific ways a thermodynamic system can be arranged, reflecting the amount of uncertainty or the number of possible microstates corresponding to a given macrostate. Entropy quantifies disorder, with higher entropy indicating greater disorder. According to the second law of thermodynamics, the entropy of an isolated system never decreases, meaning natural processes tend to move toward a state of maximum entropy or disorder. Entropy also measures the irreversibility of processes, where spontaneous processes increase the entropy of the universe. It is a key factor in determining the efficiency of heat engines and refrigerators, understanding the behavior of biological systems, and studying the evolution of the universe. In essence, entropy is a measure of the unpredictability and energy dispersion in a system, providing insight into the natural tendency towards disorder and the limitations of energy conversion.

Variables

Calculations

Calculations

Equations

Examples

To better understand the concept of entropy, we can imagine a system in a solid state, where atoms are arranged in an orderly manner and entropy is low.

As energy is supplied to the system, the atoms begin to oscillate with greater amplitude, and the order gradually breaks down. Upon reaching the melting temperature, some particles are released from their fixed positions and gain greater freedom of movement within the matrix of the material. This increased disorder leads to a rise in entropy.

As we continue supplying energy and reach the boiling point, particles begin to escape from the system, transitioning into the gaseous state. This is the state with the greatest molecular freedom and disorder, and thus the highest entropy. Finally, when the system fully evaporates, it reaches its maximum entropy for this transformation.

If we consider the equation of the differential inexact labour ($\delta W$) with the mechanical force ($F$) and the distance traveled ($dx$):

in its form of the pressure ($p$) and the volume ($V$):

Work plays the role of a potential, while the pressure ($p$) acts as a 'generalized force,' and the volume ($V$) serves as the path, a kind of 'independent variable.' If we organize these concepts into a matrix for the parameters we have discussed so far, we get:

| Thermodynamic Potential | Generalized Force | Independent Variable |

| Extensive | Intensive | Extensive |

| $\delta W$ | $p$ | $dV$ |

| $\delta Q$ | $T$ | $?$ |

In this context, we see that for the line the variation of heat ($\delta Q$), we have the variable the absolute temperature ($T$), but we lack an extensive independent variable. We will call this entropy and denote it with the letter $S$.

There are variables that are associated with quantities, while others are associated with properties.

• The first ones are called extensive variables, as they can be extended or increased in proportion to the amount of substance present. Examples of extensive variables include volume, mass, electric charge, heat, and so on.

• On the other hand, the second ones are called intensive variables, which represent properties that do not depend on the quantity of substance present. These properties remain unchanged regardless of the amount of substance. Examples of intensive variables include density, pressure, temperature, and so on.

If the entropy is estimated as a function of temperature, the following observations can be made:

• In each phase (solid, liquid, gas), entropy tends to slightly increase with temperature.

• During phase transitions, there is a significant jump in entropy.

This can be represented as:

In this way, entropy can be understood as an average measure of the degrees of freedom that a system possesses. In each phase, entropy gradually increases as a few additional degrees of freedom are \\"released\\". However, during phase transitions, the increase in entropy is dramatic. In a solid, multiple bonds restrict the movement of atoms, resulting in limited degrees of freedom. In a liquid, many bonds are broken, creating new freedoms that allow for relative movement, leading to numerous new degrees of freedom. Finally, in the transition to the gas phase, all bonds are lost, and each particle has its three degrees of freedom. As the temperature increases further, particles can rotate and oscillate, introducing new degrees of freedom and additional increases in entropy.

If we consider two identical systems, one with a temperature $T_1$ and the other with a temperature $T_2$, their entropies can be calculated using the equation involving the entropy ($S$), the absolute temperature ($T$), the caloric Capacity ($C$), the base entropy ($S_0$), and the base temperature ($T_0$):

Therefore, the entropies will be:

$S_1 = S_0 + C\log\left(\displaystyle\frac{T_1}{T_0}\right)$

and

$S_2 = S_0 + C\log\left(\displaystyle\frac{T_2}{T_0}\right)$

If both systems are mixed, their temperature will be the average temperature:

$T_m=\displaystyle\frac{1}{2}(T_1+T_2)$

Therefore, the entropy of the new system will be:

$S_{1+2}=2S_0+2C\log\left(\displaystyle\frac{T_m}{T_0}\right)=2S_0+2C\log\left(\displaystyle\frac{T_1+T_2}{2T_0}\right)$

The entropy of the new system is greater than the sum of the individual entropies:

$\Delta S=2C\log\left(\displaystyle\frac{T_1+T_2}{2T_0}\right)-C\log\left(\displaystyle\frac{T_1}{T_0}\right)-C\log\left(\displaystyle\frac{T_2}{T_0}\right)$

If we graph $\Delta S/C$ as a function of $T_1/T_0$ and $T_2/T_0," we obtain the following figure:

$\Delta S/C$ is nearly zero if the temperatures are very similar ($T_1\sim T_2$). However, if the temperatures are different, entropy will always increase. If we study this in other systems, we will observe that whenever an irreversible change occurs, entropy increases. Mixing is irreversible, meaning the system will not return to its initial state without external intervention. In other words, the system will not spontaneously separate into two subsystems with completely different temperatures.

If the temperatura de fusión ($T_f$) represents the boiling temperature, the molar entropy of the liquid ($s_L$) corresponds to the molar entropy of the liquid, and the molar entropy of the solid ($s_S$) to that of the solid, then the enthalpy of evaporation the calor latente molar del cambio de fase solido liquido ($l_S$) is calculated using the following formula:

If the boiling temperature ($T_b$) is the boiling temperature, the molar entropy of the gas (or vapor) ($s_G$) represents the molar entropy of the vapor, and the molar entropy of the liquid ($s_L$) represents that of the liquid, then the enthalpy of evaporation the calor latente molar del cambio de fase liquido vapor ($l_V$) is calculated using the following expression:

The value of the molar entropy ($s$) is determined as a function of the reference molar entropy ($s_0$), depending on the molar specific heat ($c$), ERROR:5199, and the base temperature ($T_0$), according to:

The value of the molar entropy ($s$) is determined as a function of the reference molar entropy ($s_0$), depending on the molar specific heat ($c$), ERROR:5199, and the base temperature ($T_0$), according to:

The value of the molar entropy ($s$) is determined as a function of the reference molar entropy ($s_0$), depending on the molar specific heat ($c$), ERROR:5199, and the base temperature ($T_0$), according to:

The value of the molar entropy ($s$) is determined as a function of the reference molar entropy ($s_0$), depending on the molar specific heat ($c$), ERROR:5199, and the base temperature ($T_0$), according to:

The value of the molar entropy ($s$) is determined as a function of the reference molar entropy ($s_0$), depending on the molar specific heat ($c$), ERROR:5199, and the base temperature ($T_0$), according to:

ID:(1471, 0)