Difusión

Definition

La difusión se origina por la diferencia de concentración de las partículas. Si otras palabras, al existir un numero mayor de partículas en una zona respecto de una segunda existe una mayor probabilidad que pase de esta a la segunda que a la inversa.

ID:(12139, 0)

Calculo de concentraciones

Image

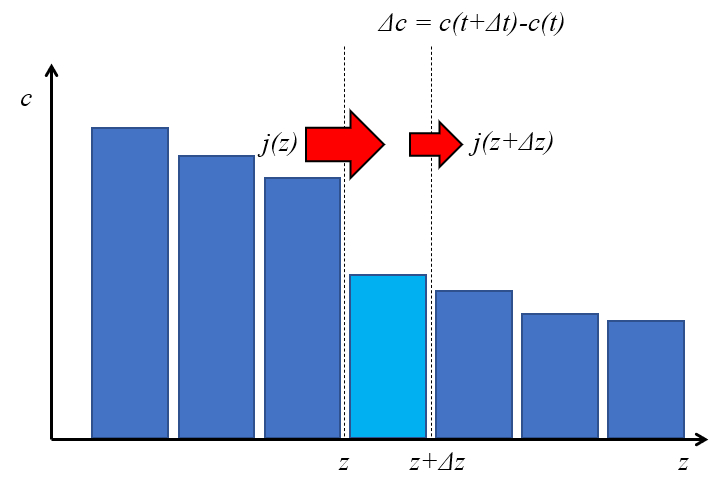

Para determinar la concentración en un punto se necesita calcular las cantidades que ingresan y las que salen de un volumen. Por ello para un espacio entre dos posición se considera el flujo que entra en restar lo que sale. Por ello la variación de la cantidad es igual a la concentración por el largo del segmento que es a su vez igual a el flujo por el tiempo considerado:

ID:(12141, 0)

Forma de la distribución

Note

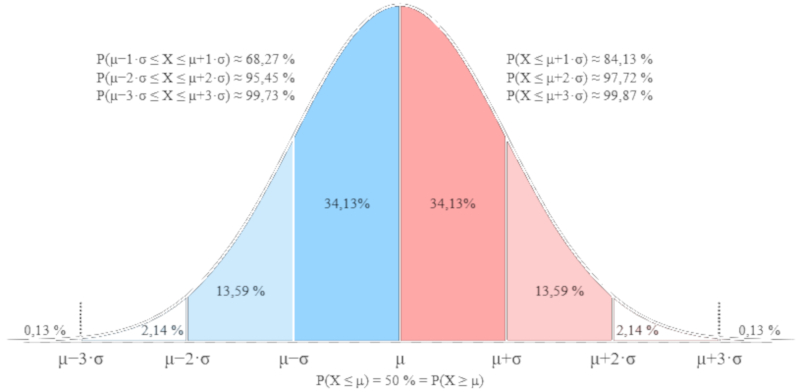

La distribución obtenida corresponde con a :

| $ c =\displaystyle\frac{1}{\sqrt{4\pi D t }} e^{- z ^2/4 D t }$ |

que corresponde a una distribución de Gauss y que se muestra a continuación.

ID:(12142, 0)

Diffusion processes

Storyboard

Diffusion occurs when there is a difference in concentration between regions, causing particles to move from areas of higher concentration to those of lower concentration. The resulting flow depends on the magnitude of that difference and the distance over which it occurs. By analyzing how this flow changes between two points over time, one arrives at an expression that describes how concentration changes locally. When the rate of diffusion is constant, this expression simplifies and describes a bell-shaped distribution that evolves with time and position. This distribution becomes wider as time passes, while its peak height decreases proportionally.

Variables

Calculations

Calculations

Equations

The flux density ($j$) depends on the diffusion constant ($D$) and on the gradient, which is estimated from the variación de la concentración ($\Delta c$) and the distance ($\Delta z$):

In the limit where discrete intervals become infinitesimal differentials ($\Delta z \arrowright dz$), the following is obtained for the concentration ($c$) and the position ($z$):

The variación de la concentración ($\Delta c$) varies with the duration of time ($\Delta t$) as a function of the variation of flux density ($\Delta j$), which in turn depends on the distance ($\Delta z$):

In the limit where discrete intervals become infinitesimal differentials ($\Delta z \rightarrow dz$, $\Delta t \rightarrow dt$), the following is obtained for the concentration ($c$), the flux density ($j$), the position ($z$), and the time ($t$):

Fick's second law states that the variation of the concentration ($c$) with respect to the time ($t$) is equal to the variation of the flux density ($j$) with respect to the position ($z$):

which, using the relation for the flux density ($j$),

results in the diffusion equation:

Fick's second law, which relates the concentration ($c$), the diffusion constant ($D$), the position ($z$), and the time ($t$), is expressed as follows:

When the diffusion constant ($D$) is constant, this equation simplifies to:

The differential equation governing the concentration ($c$), assuming the diffusion constant ($D$) is constant, is expressed as a function of the position ($z$) and the time ($t$):

whose solution is:

In the case of diffusion with constant the diffusion constant ($D$), the distribution of the concentration ($c$) as a function of the position ($z$) and the time ($t$) takes the following form:

By introducing the standard deviation ($\sigma$) in the form:

the distribution can be rewritten as:

The concentration ($c$) is influenced by the speed of the medium ($u$), which acts in opposition to the diffusion process characterized by the diffusion constant ($D$) in the positive the position ($z$) region, thereby modifying the distribution in the time ($t$) according to:

The solution to this equation has the following form:

Examples

Diffusion arises from differences in particle concentration. In other words, when there are more particles in one region than in another, there is a higher probability that they will move from the region of higher concentration to the one with lower concentration, rather than the other way around.

In a liquid or gas, situations may arise where the concentration of a given property (such as a substance, heat, or momentum) is not uniform.

In such cases, particles carrying that property are more likely to move from regions of higher concentration to those of lower concentration, simply because there are more of them in the former. As a result, the flux depends both on the concentration difference and the distance over which that difference occurs in other words, it depends on the concentration gradient.

If the concentration at a point $z$ in a solution is $c(z)$ and at another point $z + \Delta z$ is $c(z + \Delta z)$, then according to the variación de la concentración ($\Delta c$):

$\Delta c = c(z + \Delta z) - c(z)$

This defines a gradient as per the distance ($\Delta z$):

$\displaystyle\frac{c(z + \Delta z) - c(z)}{\Delta z} = \displaystyle\frac{\Delta c}{\Delta z} \sim \displaystyle\frac{\partial c}{\partial z}$

According to the flux density ($j$), the flux is proportional to this gradient, and the proportionality constant is called the diffusion constant ($D$).

Thus, we obtain:

This equation is known as Ficks First Law.

To obtain an expression for the flux at a point rather than an average value the infinitesimal limit of the differentials of flux is considered. In this case, the flux density ($j$), as a function of the diffusion constant ($D$), the variación de la concentración ($\Delta c$), and the distance ($\Delta z$), is expressed as:

This limit leads to the so-called Ficks First Law, which, in its continuous form and written in terms of the concentration ($c$) and the position ($z$), is given by:

To determine the concentration at a point, it is necessary to calculate the amounts entering and leaving a control volume. Therefore, in a space defined between two positions, the incoming flow is considered minus the outgoing flow. The change in the contained amount is then equal to the concentration multiplied by the length of the segment, which in turn is equivalent to the net flow times the time interval considered.

If an element of the distance ($\Delta z$) is considered over a time interval the duration of time ($\Delta t$), then according to the flux density ($j$):

• At position $z$, a flow of $j(z), \Delta t$ enters

• At position $z + \Delta z$, a flow of $j(z + \Delta z), \Delta t$ exits

According to the variation of flux density ($\Delta j$), the variation in the element's content is $\Delta c, \Delta z$.

Therefore, the mass balance is expressed as:

$ \Delta c, \Delta z = \left[-j(z) + j(z + \Delta z)\right] \Delta t = -\Delta j, \Delta t $

This leads to the following fundamental relation:

To obtain the concentration at a specific point, it is necessary to move from the averaged form to the local (pointwise) version. Using the variation of flux density ($\Delta j$), the variación de la concentración ($\Delta c$), the distance ($\Delta z$), and the duration of time ($\Delta t$), the starting equation is:

Taking the infinitesimal limit leads to the differential form corresponding to Ficks Second Law. This, in terms of the flux density ($j$), the concentration ($c$), the position ($z$), and the time ($t$), is expressed as:

In the 19th century, several transport phenomena were already known, such as heat conduction described by Fourier in 1822, fluid hydrodynamics developed from the NavierStokes equations, and biological processes like osmosis, in which the movement of substances was observed without a visible flow.

Adolf Fick noticed that mass diffusionfor example, the diffusion of oxygen in tissuesseemed to behave similarly to heat conduction. In 1855, directly inspired by Fouriers law, Fick proposed an analogy for diffusion, formulating what is now known as his first law, where mass flux is proportional to the concentration gradient. This law allowed him to describe the transport of salt or gases through semipermeable membranes and biological tissues. Later, to study how concentration changes over time, Fick combined this law with the principle of mass conservation, leading to what is now known as Ficks second law, which describes the spatiotemporal evolution of concentration in a diffusive medium. He applied these laws mainly to the analysis of gas transport in tissues, particularly to the diffusion of oxygen in the cornea and of salts through biological membranes.

[1] Adolf Fick (1829-1901) by the painter Anton Klamroth

[2] " ber Diffusion" (1855), published in Annalen der Physik

Ficks law in its general form, involving the concentration ($c$), the diffusion constant ($D$), the position ($z$), and the time ($t$), is given by:

When the diffusion coefficient the diffusion constant ($D$) is constant, this equation simplifies to:

In the case where the diffusion constant ($D$) is constant, Fick's general law simplifies and allows the concentration ($c$) to be expressed as a function of the position ($z$) and the time ($t$):

By solving this equation, the following analytical expression is obtained:

The resulting distribution for the concentration ($c$), as a function of the diffusion constant ($D$), the position ($z$), and the time ($t$), is given by:

This expression corresponds to a Gaussian distribution, shown below:

The width of the distribution is determined by the factor the standard deviation ($\sigma$), which corresponds to the standard deviation of the distribution and can be calculated as the square root of the diffusion constant ($D$) and the time ($t$), according to:

This means that the width increases with the square root of time, while the central height decreases inversely with this factor.

The concentration ($c$) represents a distribution that depends on the diffusion constant ($D$) and is expressed as a function of the position ($z$) and the time ($t$):

Since the time ($t$) is related to the diffusion constant ($D$) through the standard deviation ($\sigma$), by:

this leads to:

The concentration ($c$) is influenced by the speed of the medium ($u$), which acts in opposition to the diffusion process described by the diffusion constant ($D$) in the positive the position ($z$) region, thereby altering the distribution in the time ($t$) according to:

In the case where the speed of the medium ($u$) is constant, the following solution is obtained:

where the function erf, or Gaussian error function, appears:

This solution implies that the point where the concentration reaches half of its initial value moves over time with the flow velocity, according to:

$z = u t$

Moreover, the concentration profile becomes flatter over time, since the width of the transition zone depends on the standard deviation:

The flux density ($j$) depends on the diffusion constant ($D$) and on the gradient, which is estimated from the variación de la concentración ($\Delta c$) and the distance ($\Delta z$):

According to Ficks First Law, the flux density ($j$) is a function of the diffusion constant ($D$), the concentration ($c$), and the position ($z$), and is expressed as:

The variación de la concentración ($\Delta c$) varies with the duration of time ($\Delta t$) as a function of the variation of flux density ($\Delta j$), which in turn depends on the distance ($\Delta z$):

Ficks Second Law states that the variation of the concentration ($c$) with respect to the time ($t$) is equal to the variation of the flux density ($j$) with respect to the position ($z$):

Ficks Second Law, which relates the concentration ($c$), the position ($z$), the diffusion constant ($D$), and the time ($t$), is expressed as:

Ficks law in its general form, involving the concentration ($c$), the diffusion constant ($D$), the position ($z$), and the time ($t$), is given by:

The concentration ($c$) represents a distribution that depends on the diffusion constant ($D$) and is expressed as a function of the position ($z$) and the time ($t$):

The standard deviation ($\sigma$) defines the width of the distribution, which depends on the diffusion constant ($D$) and increases with the square root of the time ($t$), according to:

The concentration ($c$) represents a distribution that depends on the standard deviation ($\sigma$) and is expressed as a function of the position ($z$):

The concentration ($c$) is influenced by the speed of the medium ($u$), which acts against the diffusion process characterized by the diffusion constant ($D$) in the positive the position ($z$) region, thereby affecting the distribution in the time ($t$) according to:

The concentration ($c$) is influenced by the speed of the medium ($u$), which acts against the diffusion process characterized by the diffusion constant ($D$) in the positive the position ($z$) region, thereby affecting the distribution in the time ($t$) according to:

ID:(1624, 0)