Turbulent flow through tubes

Storyboard

If the Reynolds number exceeds 2000, the flow in a tube always becomes unstable and eventually becomes fully turbulent. As a result, it is no longer possible to use the viscous laminar flow approximation that gives rise to the Hagen-Poiseuille law, and an alternative model is required.

The model that describes a flow where viscosity is irrelevant is the one that gives rise to Bernoulli's equation. However, this model assumes that energy density is conserved. An alternative is to assume that turbulence leads to mixing in such a way that energy density is not conserved but remains constant. In this case, the flow can be modeled using an equation similar to Bernoulli's, but with a correction to account for homogenization due to mixing effects.

ID:(1970, 0)

Flow at the laminar boundary

Note

If we replace the Darcy-Weisbach friction factor in the laminar limit, given by

| $ f_D = \displaystyle\frac{64}{ Re }$ |

in the Darcy-Weisbach equation, represented as

| $ \Delta p = \displaystyle\frac{ \Delta L }{ D_H } f_D \displaystyle\frac{1}{2} \rho_w j_s ^2 $ |

and employ the definition of the Reynolds number $Re$, we can demonstrate that the flow is governed by

| $ J_V =-\displaystyle\frac{ \pi R ^4}{8 \eta }\displaystyle\frac{ \Delta p }{ \Delta L }$ |

which corresponds to the Hagen-Poiseuille equation.

ID:(14530, 0)

Turbulent flow through tubes

Description

If the Reynolds number exceeds 2000, the flow in a tube always becomes unstable and eventually becomes fully turbulent. As a result, it is no longer possible to use the viscous laminar flow approximation that gives rise to the Hagen-Poiseuille law, and an alternative model is required. The model that describes a flow where viscosity is irrelevant is the one that gives rise to Bernoulli's equation. However, this model assumes that energy density is conserved. An alternative is to assume that turbulence leads to mixing in such a way that energy density is not conserved but remains constant. In this case, the flow can be modeled using an equation similar to Bernoulli's, but with a correction to account for homogenization due to mixing effects.

Variables

Calculations

Calculations

Equations

If there is the pressure difference ($\Delta p$) between two points, as determined by the equation:

| $ dp = p - p_0 $ |

we can utilize the water column pressure ($p$), which is defined as:

| $ p_t = p_0 + \rho_w g h $ |

This results in:

$\Delta p=p_2-p_1=p_0+\rho_wh_2g-p_0-\rho_wh_1g=\rho_w(h_2-h_1)g$

As the height difference ($\Delta h$) is:

| $ \Delta h = h_2 - h_1 $ |

the pressure difference ($\Delta p$) can be expressed as:

| $ \Delta p = \rho_w g \Delta h $ |

(ID 4345)

Flow is defined as the volume the volume element ($\Delta V$) divided by time the time elapsed ($\Delta t$), which is expressed in the following equation:

| $ J_V =\displaystyle\frac{ \Delta V }{ \Delta t }$ |

and the volume equals the cross-sectional area the section Tube ($S$) multiplied by the distance traveled the tube element ($\Delta s$):

| $ \Delta V = S \Delta s $ |

Since the distance traveled the tube element ($\Delta s$) per unit time the time elapsed ($\Delta t$) corresponds to the velocity, it is represented by:

| $ j_s =\displaystyle\frac{ \Delta s }{ \Delta t }$ |

Thus, the flow is a flux density ($j_s$), which is calculated using:

| $ j_s = \displaystyle\frac{ J_V }{ S }$ |

(ID 4349)

The original solution by S.E. Haaland is as follows:

$\displaystyle\frac{1}{\sqrt{f_D}}=-1.8\log\left(\left(\displaystyle\frac{\epsilon/R_H}{12}\right)^{1.11} + \displaystyle\frac{6.9}{Re}\right)$

It can be rearranged to obtain the expression for the Darcy-Weisbach friction factor $f_D$ as follows:

| $ f_D = \displaystyle\frac{25}{81 \log\left(\left(\displaystyle\frac{ \epsilon }{12 R_H }\right)^{1.11} + \displaystyle\frac{6.9}{ Re }\right)^2}$ |

(ID 14534)

The original solution by S.E. Haaland is as follows:

$\displaystyle\frac{1}{\sqrt{f_D}}=-1.8\log\left(\left(\displaystyle\frac{\epsilon/D_H}{3.7}\right)^{1.11} + \displaystyle\frac{6.9}{Re}\right)$

It can be rearranged to obtain the expression for the Darcy-Weisbach friction factor $f_D$ as follows:

| $ f_D = \displaystyle\frac{25}{81 \log\left(\left(\displaystyle\frac{ \epsilon }{3.7 D_H }\right)^{1.11} + \displaystyle\frac{6.9}{ Re }\right)^2}$ |

(ID 14535)

The section or Area ($S$) of the tube containing the liquid can be expressed as a function of the depth in an unfilled tube ($h$) by integrating over the radius up to the tube radius ($R$):

$S = 2\displaystyle\int_0^h dz \sqrt{2Rz - z^2}=\displaystyle\frac{1}{2}(R-h)\sqrt{2Rh - h^2}+\displaystyle\frac{1}{2}R^2\arcsin\left(\displaystyle\frac{1-h}{R}\right)$

If we expand this expression in terms of the factor $h/R$ in the limit $h\ll R$, we obtain, to first order:

$S = \sqrt{\displaystyle\frac{2^3}{3^2} R h ^3}$

If we solve for the depth, we finally obtain:

| $ h = \left(\displaystyle\frac{3^2 S^2 }{2^3 R }\right)^{1/3}$ |

(ID 14541)

Since the angle between the radius at the edge of the liquid surface and the vertical can be calculated using the depth in an unfilled tube ($h$) and the tube radius ($R$) as:

$\phi =\arccos\left(1-\displaystyle\frac{h}{R}\right)$

The corresponding arc is $R\phi$, so the total arc is:

$2 R \arccos\left(1-\displaystyle\frac{h}{R}\right)$

Similarly, half of the surface area can be determined using the Pythagorean theorem, which results in:

$\sqrt{2Rh - h^2}$

Therefore, the hydrodynamic perimeter ($P_H$) is expressed as:

$P_H = 2\sqrt{2Rh - h^2}+2R\arcsin\left(1-\displaystyle\frac{h}{R}\right)$

In the limit of a small height, where $h\ll R$, this expression can be expanded, resulting in:

| $ P_H = \sqrt{2^5 R h }$ |

(ID 14542)

Examples

When modeling flow in a pipe, assuming that the energy density is conserved, we obtain Bernoullis equation. This equation describes the flow using the pressure difference ($\Delta p$) in terms of the liquid density ($\rho_w$), the mean Speed of Fluid ($v$), and the speed difference between surfaces ($\Delta v$):

| $ \Delta p = - \rho \bar{v} \Delta v $ |

In the case of turbulent flow, the mixing process acts as a friction that reduces the velocity gradient present in laminar flow between the center and the pipe walls. If we assume that this mixing effect can be modeled by a simple correction factor, we empirically arrive at the Darcy-Weisbach equation, which involves the darcy-Weisbach friction factor ($f_D$), the tube length ($\Delta L$), and the hydrodynamic diameter ($D_H$):

| $ \Delta p = \displaystyle\frac{ \Delta L }{ D_H } f_D \displaystyle\frac{1}{2} \rho_w j_s ^2 $ |

The factor the darcy-Weisbach friction factor ($f_D$) has been determined empirically for various flow conditions and is expressed as a function of the number of Reynold ($Re$).

(ID 15893)

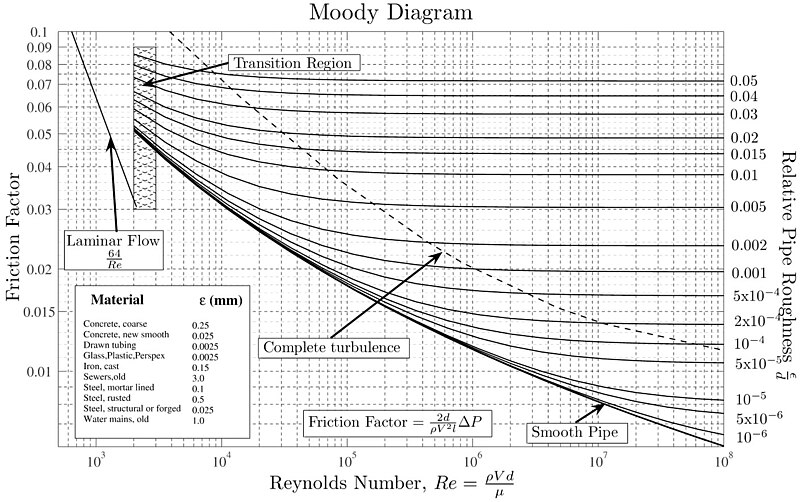

In 1944, Lewis Ferry Moody measured the Darcy-Weisbach friction factor as a function of the Reynolds number and the relative roughness of the wall, resulting in the creation of the following diagram:

The relative roughness can be estimated by considering the size of surface irregularities (height of protrusions or depths of grooves) in relation to the hydraulic diameter.

Two distinct behaviors are observed:

• For Reynolds numbers below 2000, the Darcy-Weisbach friction factor depends solely on the Reynolds number, following a relationship of $64/Re$. This corresponds to the laminar flow regime.

• For Reynolds numbers above 2000, a behavior is observed that depends on both the Reynolds number and the relative roughness of the tube's surface.

(ID 14528)

In the context of the Darcy-Weisbach equation, a hydrodynamic diameter ($D_H$) is used, which corresponds to a generalization of the traditional diameter of a circle. This allows us to consider a non-circular section and calculate an equivalent diameter based on the area of the section Tube ($S$) and its the perimeter ($P$) using the following formula:

| $ D_H = \displaystyle\frac{ 4 S }{ P }$ |

For a circular section, we obtain the traditional diameter of a circle as follows:

$D_H = \displaystyle\frac{4 S}{P} = \displaystyle\frac{4 \pi R^2}{2 \pi R} = 2R$

(ID 15894)

In the context of the Darcy-Weisbach friction factor, a hydraulic radius ($R_H$) is used, which is a generalization of the traditional radius of a circle. This allows us to calculate a diameter based on the area of the section Tube ($S$) and its perimeter in contact with the hydrodynamic perimeter ($P_H$), using the following formula:

| $ R_H = \displaystyle\frac{ S }{ P_H }$ |

For a circular section, we can obtain the traditional hydraulic radius of a circle as follows:

$R_H = \displaystyle\frac{S}{P} = \displaystyle\frac{\pi R^2}{2 \pi R} = \displaystyle\frac{1}{2} R$

(ID 15895)

In a cylindrical tube, the depth is related to the flow as follows:

By integrating the section or Area ($S$), we can calculate how the surface area varies with the depth in an unfilled tube ($h$) through the integral over the radius up to the tube radius ($R$), which gives:

$S = 2\displaystyle\int_0^h dz \sqrt{2Rz - z^2}=\displaystyle\frac{1}{2}(R-h)\sqrt{2Rh - h^2}+\displaystyle\frac{1}{2}R^2\arcsin\left(\displaystyle\frac{1-h}{R}\right)$

For small flows, where the depth is significantly less than the radius, the relationship between the cross-sectional area and the depth simplifies considerably. Solving the depth equation gives:

| $ h = \left(\displaystyle\frac{3^2 S^2 }{2^3 R }\right)^{1/3}$ |

(ID 15896)

The hydrodynamic perimeter ($P_H$) in a partially filled tube corresponds to the edges of the section in contact with the liquid, meaning the arc that touches both the wall of the tube and the surface:

Thus, it can generally be expressed as a function of the tube radius ($R$) and the depth in an unfilled tube ($h$) as:

$P_H = 2 R \arccos\left(1-\displaystyle\frac{h}{R}\right) + 2\sqrt{2Rh-h^2}$

For small flows, where the depth is significantly smaller than the radius, this simplifies the relationship between the cross-sectional area and the depth to:

| $ P_H = \sqrt{2^5 R h }$ |

(ID 15897)

If we replace the Darcy-Weisbach friction factor in the laminar limit, given by

| $ f_D = \displaystyle\frac{64}{ Re }$ |

in the Darcy-Weisbach equation, represented as

| $ \Delta p = \displaystyle\frac{ \Delta L }{ D_H } f_D \displaystyle\frac{1}{2} \rho_w j_s ^2 $ |

and employ the definition of the Reynolds number $Re$, we can demonstrate that the flow is governed by

| $ J_V =-\displaystyle\frac{ \pi R ^4}{8 \eta }\displaystyle\frac{ \Delta p }{ \Delta L }$ |

which corresponds to the Hagen-Poiseuille equation.

(ID 14530)

ID:(1970, 0)